Creating Media for Blended Learning

The area that I’m keen to reflect on and discuss as a specialism is the production of multi-media to support teaching and learning. In my role as Lead for Media Development in ILIaD I manage a team who are able to design learning objects and work with filmmakers and rapid developers who are able create digital assets to support these projects.

Blended Learning is, according to some, ‘the thoughtful fusion of face-to-face and online learning experience’ ¹. Is there such a thing as a perfectly blended course? There is much debate as to the degree that a course is blended and whilst flipped learning can be seen as a model approach for blended learning, it pretends a 50/50 split between online activity and f2f. It’s an idealised model which is often spoken about but seldom seen. If an educator chooses to make the move to blended learning, then it has to be incremental and planned. Educators should feel that they’re making progress if every time they are able to adopt technology into delivery the learner is rewarded. At Southampton it’s important to recognise a small change that can bring huge benefit, whether that’s creating an account through social media learners can communicate through or creating a series of videos to support ideas or theories.

A recent post on Medium provides a guide for academics and contributors designing and preparing digital objects to support learning.

Case Study – Dr Scott Border – Anatomy

- Scott developed an ebook designed to facilitate student’s learning in the laboratory.

- A key innovation has been Soton Brain Hub – a YouTube channel for neuroanatomy with videos and screencast lectures.

- The team then use Twitter to provide links to these educational resources at an appropriate time to impact the students learning.

- These techniques helped students being proactive in their learning – blending their own learning experience.

Planning and Preparation

There are a number of steps in the process of creating and delivering learning objects and it is important to discuss some of the requests and needs that are expressed by educators and researchers.

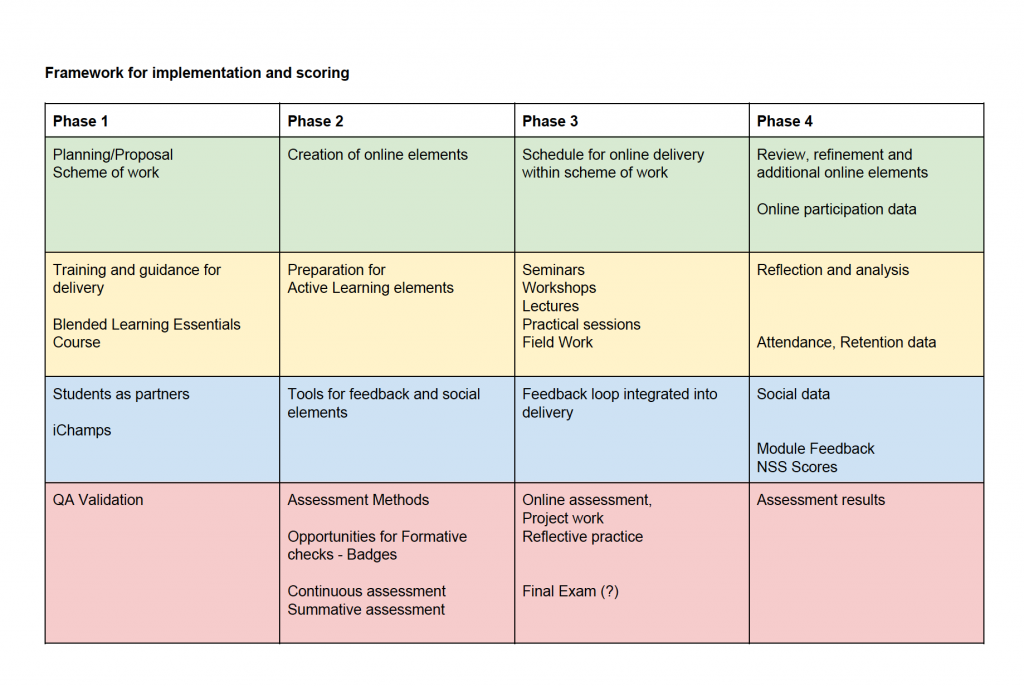

Recently, I have set out my thoughts regarding a process for adopting a blended approach and a breakdown of the steps and phases that would guide an educator. My belief is in a process that brings together the four key stakeholders – Educator, Education Developer (or Learning Designer), Learners, and Quality Assurance; and takes them through four phases of planning, creation, implementation and review.

It’s importance to establish an understanding of the way our teams of learning designers and media specialists support the process, taking the other areas into consideration and tying everything to Learning Outcomes. The next stage was to look at a system for scoring the progress and therefore measuring the degree of adoption.

Creating media-rich resources for teaching and learning

In many cases the first interaction is a simple request for a particular digital asset, whether thats a video or audio recording, an articulate object, an animation or graphic or diagram. It is important to drill down to the need for this asset, this is crucial in terms of being able to create something that is effective. Often the asset has been requested because it has been identified as a solution to a wider issue or need. Often the drivers for these assets are rooted within change objectives.

- Scalability of delivery – moves to blended learning

- Expanding access to learning resources

- Capturing one-time learning opportunities – guest lecturers, unique events and experiments.

- Sharing learning opportunities and reflective learning.

- Capturing evidence – student submission

A note about scalability, in this context it is about the number of course modules that have not been designed or adapted in order to be delivered in a blended way. In an institution like Southampton, there are in the region of two-thousand programmes of study, so we need a rate of change that is achievable and sustainable. I too am fearful about the idea of scalability that really means an automation of education delivery and it is important to sense check whether a framework or process leads to commodification or a one-size fits all approach.

The next step in the conversation is to meet with the educator to discuss the wider requirement. If we are looking to create a learning object, the most important aspect is to identify the learning outcome. There are often times when this has not been identified in a meaningful way and it’s clear that the asset requested is not appropriate. It is important that the rationale for the learning object is clear and well-stated. There are many occasions when I have suggested something different. For instance:

- Videos of a duration longer that 3-5 minutes have very low viewing figures.

- Audio Podcasts are much more successful for long-form broadcast

- Videos of talking heads are less engaging (according to student feedback) than demonstrations or illustrations.

- Showing not telling should be the motivation for any script or plan.

- Educators are not necessarily natural storytellers for camera or podcast recording, they need to be trained and supported.

- Videos need to be shared, broadcast, disseminated to a wide audience – projection of viewing figures is too often based on hope rather than a good plan for attracting an audience.

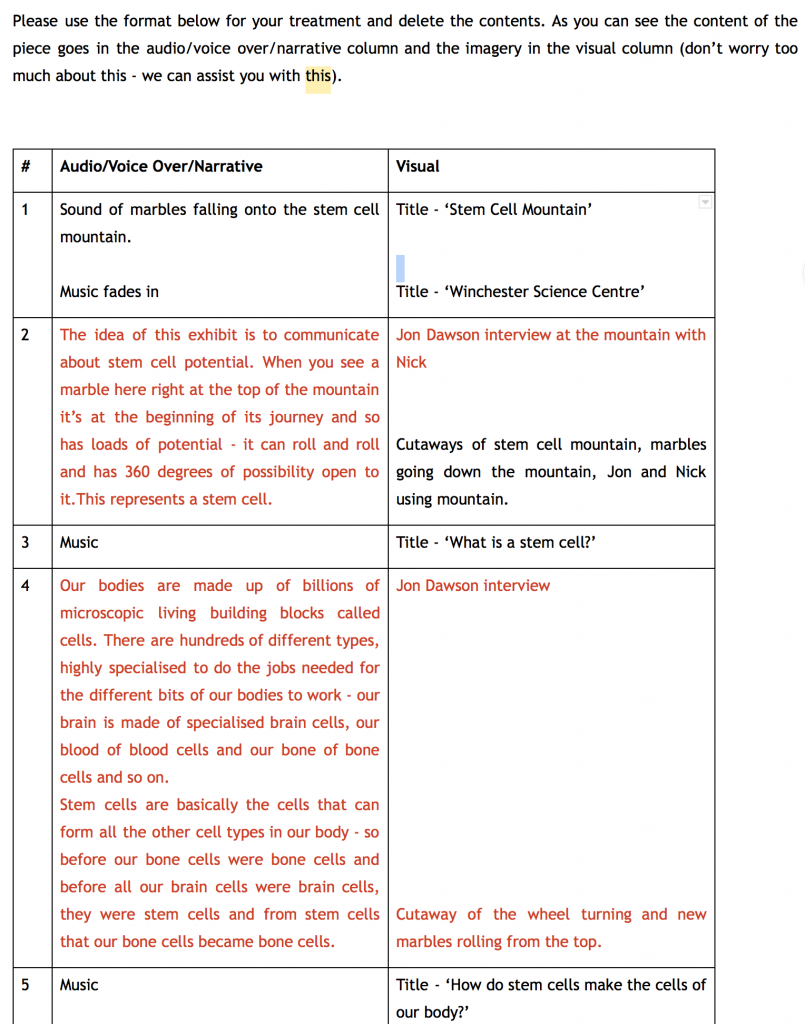

If we move to the next stage, a script will support the production. Often I will send an example (as below) with some simple guidance, using Google Docs in order to invite collaboration.

Production

The key to successful production is preparation. It is sometimes difficult to convince experienced educators who have taught and lectured in front of large classes, but have less experience of creating video or recording podcast; that it is an entirely different proposition. To a certain extent, it is similar to the difference between improvised theatre and filmmaking. The audience has to be imagined, the performance much more intimate and the text much more precise.

The team spends a great deal of time working to prepare the academic, sometimes even filming a screen test. Whereas a television presenter is chosen because of their ability to engage and connect with an audience, the primary reason for an academic or educator to put themselves in front of camera is because they are the expert. An audience is not forgiving in terms of their attention and unfortunately poor delivery and lack of charisma often leads to an ineffective learning object. If the educator or academic struggles to engage, then I might be tempted to find a presenter to take their place, however – I have found that this rarely occurs and coaching and support can be a great help in increasing the effectiveness of presentation.

Similarly settings and locations are also important, a cluttered or visually busy area can distract the viewer and a location which is too neutral or context free is a missed opportunity to create an engaging film. In other words the most effective videos are those where the location is chosen so that the educator can demonstrate or easily visualise the idea, theory or activity.

A final note is to think about the level of english language that your learner comprehends; in all these cases accessibility should be at the forefront of presentation, scripts should avoid non-specialist jargon, over-use of metaphor or simile, too many closed-cultural references or in-jokes. Again, what is accessible to those who need consideration, is accessible to all.

In this example from Developing your Research Project our online course for FutureLearn, Dr Chris Fuller talks about academic research, using jigsaw pieces to explain ideas and theories that can support the learner. This film was created by ILIaD Media Production.

Dr Fuller’s use of the jigsaw is engaging and helps provide an image that the learner can use to recall the learning aim for the video. Educators need to be encouraged to visualise ideas and create engaging imagery to support the text of their presentation.

In this short clip, Elinor Irish, Lecturer in Physics at University of Southampton uses the Explain Everything app to talk about population growth. This app records the screen and audio whilst you draw directly on a tablet, enabling you to create a short animated sequence.

Both Explain Everything and Show Me offer collaborative spaces to create whiteboard animations. Another great example is sotonbrainhub and sotonanatomyhub which use these apps as a great way to teach anatomy and brain.

The numbers game

The biggest issue currently around video creation is relationship between the amount of resource put into the production of the video versus the number of learners who watch the video. It has been challenging talking to educators and academics about this subject, there is a tension between the desire for high production values and the actual need in terms of audiences. Often it’s important to talk about an estimated number of viewers at an early stage, it is frustrating for a film to have taken two to three weeks to develop, a day to shoot, two days to edit and distribute only for a very few people to watch it. In some cases the ideas in the video will be strong enough that it can be used for a number of years, but anyone with a recollection for 1980’s Open University films on BBC will know how quickly the fashions and hair-styles of the period can date. Whilst this might not entirely disengage the viewer, the immediacy and speed with which video can be produced and disseminated, demands that video is relatively up to date, current in thinking and ideas and presented in a visual language that chimes with other recent content.

There are a number of ways an educator can maximise the opportunity for video or other digital learning object:

- ensuring that there is a test or learning check associated with the object

- ensuring that it is published across a number of platforms, including VLE, social media (incl. YouTube).

- giving ownership of the object to the students, perhaps as co-creators or co-designers.

- by revisiting the object on a regular basis

It is important that digital objects don’t fall into the same trap as large lectures, that there are numerous opportunities to engage, provide feedback, comment, share, capture ideas, adapt and collaborate. Ensure engagement, you can’t just be in broadcast mode. Digital objects that are wrapped inside a Storyline Articulate course or similar interactive system ensure the feedback and interaction are part of the experience. However, embedded objects are difficult to share and adapt. My advice would be to publish across multiple platforms, talking to the learners about their preferred channels for reading, viewing and discussion.

The role of Storytelling in research

Please click presentation left and right – includes examples of video abstracts produced by ILIaD Media Development

Above – video abstract – slide show created using swipe.to

The greatest revelation in my short time at Southampton has been working with Early Career Researchers and Research Groups. I thought that my priority would be working with educators to create digital objects for teaching and learning. However, I have found that Researchers need the same skills in digital creation and social media that educators do, if not more so. I currently run regular workshops and seminars discussing ideas around media creation and online publishing, helping individuals and groups to tell their stories and talk about their work.

There are four drivers for researchers to tell their stories:

- public engagement

- research dissemination

- reflective practice

- learning

I’ve been struck by how many researchers fail to record or capture media to support their work in any way. The opportunity provided by smart phones and tablets to quickly create a short video or audio recording, take photos, draw diagrams or write text, should be obvious. Although I feel far from achieving an understanding as to the reasons for this, I am prone to speculate that factors such as professional modesty, a feeling that “this only interests me” or even I haven’t got the time, play their part. Researchers need to be encouraged to create digital work to support their projects, examples of innovation are around digital storytelling, creating websites such as the welcome trust’s mindcraft stories or BBC4’s slow television which look at ways in which ideas can flourish and engage with thoughtful presentation.

Recently I have developed a digital badge which aims to help me triangulate the sessions with the media that my learners and attendees hopefully go on to produce. Often I would ask at the end of a session who was going to make something and all the hands went up, however, keeping track of who had made what, if anything at all became difficult, so a digital badge is awarded to those who have gone onto make something. I only have one awardee at the moment, but fingers crossed for a few more.

Recently I have developed a digital badge which aims to help me triangulate the sessions with the media that my learners and attendees hopefully go on to produce. Often I would ask at the end of a session who was going to make something and all the hands went up, however, keeping track of who had made what, if anything at all became difficult, so a digital badge is awarded to those who have gone onto make something. I only have one awardee at the moment, but fingers crossed for a few more.

One final note is the inclusion of learning as an output from research. I believe that in a research intensive institution, there is an opportunity to create a meaningful relationship between research and education, in a way that attracts students to the university, that establishes a role for research at the centre of teaching & learning, and enables the very best researchers to be able to teach and talk about their work to a wider audience.

I’m slowly understanding that this is an opportunity that isn’t there in all institutions, but I also see it as a challenge that this particular university has to rise to. Currently there is a disconnect between the two areas, one that potentially could increase with the arrival of the TEF, as universities employ specialist Teaching Fellows, rather than develop the talents of researchers. I hope that my role will afford the opportunity to bring the two areas together and exploit the potential at the heart of this relationship.

References

¹GARRISON, D. R. & VAUGHAN, N. (2008) Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines, San Francisco, Wiley.

BULLEN, P. (2004) Application to HEFCE for funding of a CETL for the Blended Learning Unit http://www.hefce.ac.uk/learning/tinits/cetl/final/show.asp?id=11

‘…the combination of traditional face-to-face teaching methods with authentic online learning activities, [which] has the potential to transform student-learning experiences and outcomes,’ (Davis and Fill, 2007:817). DAVIS, H. C. & FILL, K. (2007) Embedding blended learning in a university’s teaching culture: Experiences and reflections. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38, 817-828.